The old man sat in the corner of the one-room schoolhouse watching the ebb and flow of people coming through the front door. His dress was reminiscent of the legendary Buffalo soldiers—blue wool shirt with lighter-colored pants and a yellow scarf tied loosely around his neck. The sun, on its westward journey, sent a shaft of light along the side of his face. Smooth brown skin betrayed his 80 years; a tear, which he absentmindedly neglected to wipe away, hung tentatively on his right cheek.

“I didn’t come here to do interviews or take pictures,” he said. “I came here to talk and entertain the people.” I lowered my camera, but he didn’t speak as he watched the crowd milling around the room.

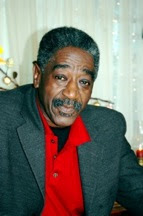

“Please don’t touch the exhibitions,” he finally admonished. “Be considerate of others coming after you.” Cornelius “Ed” Pope is no song-and-dance man, but a teacher, a griot, an elder among a group of volunteers calling itself “The Friends of Allensworth.” Neither a failing heart nor the effect of chemo treatments keeps him from his appointed task. He spearheaded the establishment of Allensworth State Park and remains a resident of Allensworth, past and present.

Fresh from the hospital, he paces himself as he greets six busloads from the Bay Area—800 visitors in all. They’re among approximately 70,000 people who tour Allensworth annually. They come to learn about the place Ed Pope is dedicated to preserving—Allensworth State Park, the vestiges of California’s first, and last, all-Black settlement.

Today’s guests come for a special day of food, music and lecture. The agenda is interesting but it is the place that matters. Fourteen refurbished historic structures survive here in the desert 35 miles north of Bakersfield. Together they represent not a dream deferred but a dream realized.

Ed Pope explained that the town was the vision of Colonel Allen Allensworth. Born into slavery he escaped to freedom as a young boy, joined the army as chaplain and moved up in the ranks. After serving in the Spanish-American War, he retired to California.

Colonel Allensworth admired Booker T. Washington’s admonitions of self-help and self-sufficiency for African Americans. From them he drew the mandate for an ideal community: One farm bought, one house built, one home sweetly and intelligently kept, one man who is the largest taxpayer or who has the largest banking account, one school or church maintained, one factory running successful, one garden profitably cultivated, one patient cured by a Negro doctor, one sermon well preached, one life clearly lived, will tell more in our favor than all the abstract eloquence that can be summoned to plead our cause.

To the surprise of Allensworth and his partner, teacher William Payne, the white-owned Pacific Farming Company offered to sell them prime land in Salito, a rural area in Tulare County. In 1908, they created the California Colony and Home Association with offices in downtown Los Angeles. These were dire times for Blacks. Jim Crow laws chewed up their recently won freedoms, and racism was rampant throughout the land.

After its 1850 statehood, California was populated by Southerners and Northerners insensitive to African Americans. Forty years prior to the creation of Allensworth, Blacks in California were denied homestead lands. The law prevented a black man from buying a plot of ground. If he managed to purchase a house and a white man claimed it, the black man could not testify against a white man in court. Blacks enjoyed no more rights in California than they did in the South. Some of these restrictions existed into the 1960s, enshrined in restrictive covenants and other forms of de-facto segregation.

Against these odds the August 7, 1908 Tulare Register reported “The Town, which is to be called Allensworth, is to enable colored people to live on an equity with whites and to encourage industry and thrift in the race.” It also declared that “Allensworth is the only enterprise of its kind in the United States.” The town was on it way.

In truth, black settlements like Allensworth were nothing new. Going back to colonial times, communities like Massachusetts’ Parting Ways sprung up in reaction to racism. There were some 50 all-black towns by the 20th century. Allensworth differed in the sense of mission and the desire of the founders to create “a thriving city on a hill,” a showcase for black accomplishment, a Tuskegee of the West. Nationwide, Blacks were starved for race victories. The birth of Allensworth was chronicled by the New York newspapers and The California Eagle proudly claimed “there is not a single white person having anything to do with the affairs of the colony.”

The Los Angeles Times described Allensworth as “an ideal Negro settlement.” And by 1913, the Oakland Sunshine, the leading Bay Area black newspaper, boasted that “the citizens of Allensworth generated nearly $5,000 a month from its business ventures.”

The town was complete with all the expected services and institutions. The Allensworth Water Company started in December 1908, followed by a school district. Classes began in a private home in 1909, but by 1910 a one-room school was up and running under William Payne’s direction. Heavy enrollment soon made it necessary to build a larger school. With funds donated by Colonel Allensworth and his wife, the old schoolhouse became a library. Soon, it was one of the state’s largest. Baptist, Methodist and Seventh Day Adventist churches saw to the citizens’ spiritual needs.

To say that racism didn’t raise its ugly head would paint a false picture. The Santa Fe Railroad refused to change the depot’s name to Allensworth, allowed Blacks to hold only the most menial jobs and eventually moved to nearby Alpough. Lack of rail service severely crippled Allensworth. Today, loaded freight trains still etch their way across the sun-baked landscape, greeted by an occasional jackrabbit.

Water soon posed another problem. The Pacific Farming Company reneged on its promise to meet Allensworth’s irrigation needs. The community sought redress through the courts and eventually gained control of the company. However, the town inherited an outdated water system at a time when they were strapped for cash. By the time they could afford to upgrade the pumping machinery, the water table had dropped below the point where the new equipment could be effective.

Attempts to build a state-supported industrial school, modeled after one established by Booker T. Washington in Alabama, also faltered. Members of both the white and black communities called the lack of county-backing racist in nature. The multiple setbacks were intensified by the loss of Colonel Allensworth. On September 13, 1914, the visionary was struck by a speeding motorcycle in Monrovia, California. He passed away the next day.

The dream didn’t die with the dreamer. Newly elected Justice of the Peace Oscar Overr and schoolteacher Payne continued to pursue innovation. To deal with the diminished water supply, some residents raised livestock instead of water-dependent crops. Others opened new businesses.

By the time Ed Pope was born in Allensworth, many citizens had had enough of a separate lifestyle that was anything but equal. As the years dragged on, some moved to Los Angeles or Oakland for jobs. The exodus intensified during World War II. In 1966 arsenic was found in the local water supply, and the population numbers continued to decline.

In 1969 Ed Pope, then a state landscape architect, and Ruth Lasartemay rallied to rescue Colonel Allensworth’s dream. They created an organization to garner support for a state historic site at Allensworth. In 1973, California purchased the land and work began. By spring 1976, plans were approved, and by October the park was dedicated.

Ed Pope grew up in Allensworth and went to school there. He credits his mentor, Mr. Heinzman, the owner of the general store, with teaching him history—especially that of Allensworth—and with instilling in him an appreciation of the Colonel’s dream.

On the day I visited it was apparent amid the picture taking and conversation that he was growing weary. He took a deep breath and pointed at the photograph of a woman who was his teacher so many years ago. Then as the late afternoon sun continued its lazy journey west, Ed Pope rested on the schoolhouse steps.

“Who,” I asked, “will continue your work? Who is going to keep teaching others about

the dream that now lives on as this park?”

“There are thousands waiting to continue where I leave off,” he answered. “The first step is to reconnect with the past. This little town is like an umbilical cord connecting to an original source. When I die, spokesmen will come out by the thousands. In fact, there are people out there right now.”

Note: An African Museum of Los Angeles’ traveling exhibit about Allensworth will open at the State Capitol’s rotunda in Sacramento February 1. It will remain there throughout Black History Month. For more information about this and other presentations visit www.caam.ca.gov.

Access Allensworth via Bakersfield with United Express service to and from Los Angeles and Denver.

Courtesy of SkyWest Magazine

Lester Sloan

Sunday, March 8, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment